By Andrew Oost

Louisville, Kentucky was never destined to be an American soccer hotbed. That the city would be home to one of the great soccer stadiums in the country, two fully professional teams, a world class training facility, an elite level youth academy, and one of the most passionate and loyal fanbases in the country is something that the most optimistic dreamer could have envisioned a few short years ago.

When Louisville’s NWSL team was announced in October of 2019, it was in many ways the culmination of the improbable process that began in 2014. That was when Louisville City FC was introduced to the world in the concourse of a minor league baseball stadium. Racing Louisville FC’s inaugural announcement occurred inside of their own brand new 14,000 seat soccer specific stadium, an striking indication of the massive leap forward that the organization had undertaken in a mere five years’ time.

Predictably, the arrival to top-flight women’s professional soccer in Louisville was greeted with open arms by the city’s soccer community. With 3,500 season tickets sold with two months remaining before Racing first takes the pitch, Louisville seems destined to be among the best supported clubs in the NWSL.

The reception from the existing NWSL community has been generally welcoming. Most observers recognize that adding high quality new clubs to a league that had only nine participants in the 2020 season is of paramount importance. Louisville fills a geographical niche in the league as well, with the next closest club in Chicago being 300 miles distant. Racing already has season ticket holders in nine different states, speaking to the void that a club in the lower midwest/upper south is able to fill for women’s soccer supporters who previously lacked a club to support.

Nevertheless, not everyone has been happy with the addition of Louisville, as there have been a vocal cadre of cynics who have doggedly criticized nearly every aspect of Racing Louisville from its inception for a variety of reasons. Racing fans have, for the most part, suffered the insults with bemusement, but recently the derision has grown loud enough to necessitate some level of redress.

Following the recent publication of an article in the Boston Globe about a federal probe into alleged visa fraud at a large youth soccer organization based out of Massachusetts, the floodgates of criticism towards Racing Louisville, and specifically head coach Christie Holly were flung wide open.

To be clear, having one’s name associated with a federal law enforcement action is never good, and there are many unresolved questions surrounding the degree of Holly’s involvement. Regardless, Holly has not been charged with any crimes, and perhaps the worst that can be said about him at this point is that he was ignorant of United States visa regulations, and that he was reckless or naive in his involvement with an organization that, if accounts are to be believed, was a shady outfit operating at the fringes of the law.

Holly is an unpopular figure in some corners of NWSL fandom, not just for the aforementioned incident, but for other more personal reasons that don’t bear discussion in this forum. So while some of the animosity directed towards Racing Louisville may in reality be a simple dislike of it’s head coach, it’s not the only source.

For many, the Louisville skepticism may have begun on day one, when management scored the equivalent of an own-goal in the first minute with the cringeworthy moniker Proof Louisville FC. The bizarre rollout of the widely mocked name may have signaled to the rest of the NWSL fanbase that perhaps Louisville wasn’t quite ready for the big leagues.

To their credit, much like what happened with Louisville City FC (twice!), management regained their senses and went back to the drawing board. Racing Louisville emerged after months of brainstorming sessions and consultations with fans, and a pride-worthy name is now attached to the club.

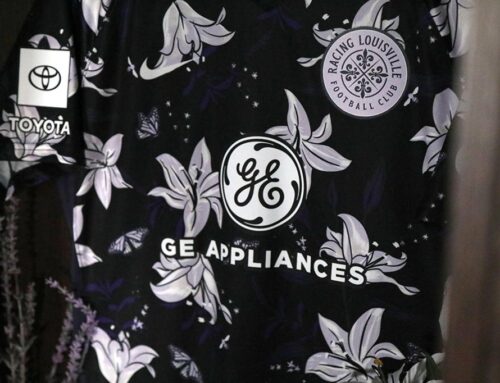

The crest that emerged from the collaboration with branding-savant Matthew Wolff is simply beautiful, and classically elegant. It’s quite possibly the best crest in the NWSL, and one of the finest in all of American soccer.

While the branding crisis was averted, the fact that Louisville, Kentucky had the gall to obtain a NWSL team before, well, any other city, really seemed to stick in the craw of people from “any other city”.

It’s true that Louisville, the 46th largest metropolitan area in the country, was granted a NWSL team before Los Angeles, the 2nd largest metropolitan area in the country. (Los Angeles has since been awarded a club, Angel City FC, slated to begin play in 2022).

It’s also true that Louisville obtained an NWSL team before Dallas, Miami, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Phoenix, San Francisco, Detroit, Minneapolis, Denver, Austin, Nashville, Cincinnati, and dozens of larger, trendier, and/or wealthier expansion cities.

How did Louisville beat so many bigger cities to the punch?

At least one prominent national soccer journalist has suggested some unscrupulousness in the fact that Amanda Duffy was the NWSL Commissioner when Louisville was awarded it’s franchise. Although Ms. Duffy clearly did not have the unilateral power to make such an important decision for the league, the fact that she was also a former employee of Louisville City seems to be an indication of smoke for those looking for a fire.

The reality is that at the time of the expansion process, Louisville was NWSL’s only suitor with a brand new world class stadium and training facilities, a preexisting passionate soccer fanbase, and a ready and willing ownership group. With nine teams spread across the entirety of the United States, NWSL is not currently in a position to bypass qualified expansion candidates. Had there been another expansion market in 2019 with all of the qualities that Louisville brought to the table, it would have been selected as well!

To suggest Ms. Duffy should have been more discriminating towards Louisville’s bid simply because she had previously been employed by them is to ignore all that Louisville had to offer as an NWSL market. It also misses the bigger question about why the league was eager to welcome a relatively small and unheralded city like Louisville into the fold.

NWSL chose Louisville because it made a serious bid, backed by an ownership group with a proven track record of success. For all it’s attributes, NWSL is a league still finding its footing, and it continues to exist in a state of precariousness. Of the founding clubs that came in with the league in 2013, only four still exist in their original form (Chicago, Portland, Sky Blue, and Washington). One team has changed ownership (OL Reign), one team has changed ownership and relocated (North Carolina), and one team has relocated twice and changed ownership twice (Kansas City to Utah, and back again to Kansas City), and one team has folded completely (Boston). Only two completely new expansion clubs have joined the league since 2013 (Houston and Orlando).

NWSL has now existed through two Women’s World Cups, and the quadriennal hype cycles that are inevitably followed by predictions that the women’s professional game is finally ready to take off. Following the US Women’s National Team’s headline stealing performance in France in 2019, it seemed a perfect time for NWSL to expand. However, after a World Cup performance that was as stylish as it was dominant, and forever memorialized by Megan Rapinoe’s iconic and defiant celebratory pose, only one city in the United States immediately stepped with a serious bid to join the NWSL: Louisville, Kentucky.

There are 27 MLS teams, and only three of them are currently invested in NWSL. The real question is why have 24 MLS owners, most of them actual billionaires, not seen fit to make the comparatively modest investment in women’s professional soccer? It would be interesting to know why the existing power brokers in American soccer, men with virtually unlimited resources, have failed to invest in the women’s game.

That is a big question, though, and one unlikely to yield easily digestible answers. For some, it’s easier to point fingers at a single unfancied newcomer than to critique the entire structure of American soccer that has failed to elevate the professional women’s game to the level that it clearly deserves.

Aside from their mere existence, Racing Louisville further ticked off the NWSL gatekeepers by having the temerity to select USWNT heroes Christen Press and Tobin Heath in the expansion draft. “They’ll never play for Louisville” has been a constant refrain ever since their selection, and while that very well may be true, Utah and Portland failed to protect their marquee players. They assumed RLFC wouldn’t have the gall to select them, and their bluff was called.

A critique of the expansion draft itself is wholly warranted. The process is unsavory on many levels, both for the players who may be forced to move against their will, and for the teams who are forced to make extremely difficult decisions about which employees to leave “unprotected”. NWSL should recognize this and develop other methods for expansion clubs to build their rosters in a way that is more fair to the players and existing teams, but that’s a topic for another day.

Nevertheless, Racing Louisville played the expansion draft game by the rules as they existed. The picks have loads of inherent value, as the rights to two of the brightest stars in women’s soccer are almost certainly worth the expenditure of two of their 16 expansion draft picks. Even if Heath and Press never play a game for Louisville, the club is now in a position to make a number of blockbuster trades. Should RLFC end up with trading their rights for another elite player (say, Rose Lavelle), or swapping for a #1 draft pick in the 2021 draft, the selections of Heath and Press will end up being an extremely shrewd bit of business.

Just days before the NWSL College Draft, it was announced Catarina Macario, the overwhelming consensus best collegiate player in the country, would be forgoing her senior season at Stanford, as well as the NWSL draft all together. Macario, whom many are calling a ‘generational’ talent and surefire USWNT star, elected to sign her first professional contract with Lyon in France rather than enter the NWSL college draft.

Lyon is the best funded, most talented, and most dominant club in women’s professional soccer in the world. While Macario’s decision to sign with the French giants was a blow to the NWSL, it was not altogether surprising. While the NWSL may hold the claim of best women’s ‘league’ in the world, Lyon is the undisputed best ‘team’, and Macario likely decided that surrounding herself with the best players on a day-to-day basis was the best way to advance her career. The paycheck probably didn’t hurt either.

That didn’t stop the disgruntled chattering classes from suggesting that Macario went to Lyon because she didn’t want to play in Louisville. Nevermind that Macario was only a junior in college, and could have simply played out her eligibility and been drafted first overall by Angel City FC the following season. To some, the reason America’s brightest prospect was leaving the country was to avoid the unbearable possibility of playing in a backwater like Louisville, Kentucky!

Racing Louisville has, in fact, gone out of it’s way to ensure that Louisville is an appealing destination for professional players. Brynn Sebring, formerly Associate General Manager of OL Reign in Seattle, was hired to be Racing’s Director of Player Experience and Operations. Sebring’s job is essentially making sure the players enjoy their time playing for RLFC both on and off the field, and to assist them with “maximizing their earnings potential”.

In a league where average salaries are under $30,000 per year, having someone on staff whose job it is to help players earn supplemental income outside of their salary is huge. Racing Louisville is the first and only club in NWSL to have such a position, and likely not the last. It’s also worth noting that Sebring sought out Racing Louisville and pitched them on the position itself. Her belief in what was being built in Louisville was what prompted her to leave one of the more long-standing and successful clubs in NWSL.

On a recent episode of Robin Pryor’s Hot Brown Soccertown podcast, Sebring addressed the perception that Louisville is a city where NWSL players wouldn’t want to play:

“Walking into Lynn Family Stadium, seeing the facilities, seeing the locker rooms, seeing the stands, seeing the field, every inch of that place is the standard that our players deserve, and that is rare in this league. I’ve been to all the stadiums, and Lynn Family Stadium is by far the best stadium in this league. That kind of investment into these women… is not happening anywhere but here.”

In an interview with the Lexington Herald-Leader, Racing Louisville forward Savannah McCaskill had the following comments regarding her early experiences in Louisville:

“Everyone that I’ve come in contact with from the club level is extremely professional, really concerned about each individual’s wellbeing, not only on the field but off the field. Our apartments are top class… you’re given everything you need while you’re here to perform… which is not the same around the league. That’s kind of a breath of fresh air that they really are doing it right here”.

Sebring recalled an anecdote about Addisyn Merrick, a Racing Louisville acquisition from North Carolina FC in the expansion draft, who stated that “my overwhelming feeling when I saw (Lynn Family) stadium was, wow, I feel like I’m a professional athlete now”. Merrick’s comment could be interpreted in several different ways, but it points to the fact that Racing Louisville is bringing a higher level of commitment and professionalism to NWSL that perhaps hasn’t always existed in the league.

Sebring said that she had heard the doubts about Louisville being a serious NWSL market, and had this to say in response:

“Mark my words, give us a couple home games at Lynn Family Stadium, just get some visiting teams in here, and it’s going to be gone. I think that by the end of the 2021 season, Louisville is going to be the place that every player is begging to play. There’s no doubt in my mind about that.”

And perhaps that is where some of the animosity towards Racing Louisville stems from, an underlying anxiety that some of the ‘old guard’ NWSL teams are going to have to evolve to keep up with a new crop of teams with higher ambitions than merely surviving.

In a league where the working conditions have not always lived up to the standards that it’s players deserve, Racing Louisville should be commended for their efforts thus far. The vocal negativity towards the club should begin to fade quickly once it becomes apparent that the fans in Louisville are amongst the loyal and supportive in the league, and that the management of the club is dedicated to making RLFC a premier destination for players. Nobody would be brazen enough to predict that Racing will be collecting hardware in the near future, but respectability is within reach.